What Is Authenticity, Really?

“Be true to yourself” is a modern mantra—but it rests on a question that has preoccupied philosophers for centuries. From Socrates to Sartre, from Rousseau to de Beauvoir, the idea of authenticity has been approached as everything from moral alignment to radical freedom. But what is the self to which we’re being true?

In coaching, leadership, and organisational life, authenticity is often treated as a personal asset—a quality to be developed, or a voice to be found. But this idea, while compelling, risks flattening the complexity of human development. What if the self we’re trying to express isn’t fixed, but emergent? What if authenticity isn’t something we discover, but something we create—in the space between ourselves and the world?

This question has shaped much of my work as a coach and supervisor. And it’s one I’ve explored more deeply through the lens of Donald Winnicott’s concept of potential space—an idea that offers a powerful way of understanding the conditions in which authenticity can arise.

The Myth of the Authentic Self

There’s a long-standing tension in Western thought between views of the self as essential (Rousseau, Maslow, Rogers) and views of the self as constructed (Nietzsche, Gergen, Sartre). Some argue that our authenticity lies in a stable inner core. Others see it as something that emerges through experience, language, and relationship.

The psychologist Stephen Wilson captures this divide in his distinction between “somatic” and “symbolic” self-processes: one rooted in felt experience, the other shaped by culture and reflection. Similarly, the philosopher Charles Taylor reminds us that identity is dialogical—formed through our interactions with others and our responses to socially shared values.

Winnicott sits in this conversation with a deceptively simple proposition:

Authenticity is not something we find, but something we create—through play, relationship, and the capacity to hold paradox.

Winnicott’s Hidden Gift to Adult Development

Winnicott’s idea of potential space was originally used to describe the intermediate zone between a mother and infant—a space where the child begins to explore the tension between fantasy and reality, self and other. In this liminal space, the infant first develops the capacity for play, imagination, and symbolic thought.

Crucially, Winnicott believed this space is not simply a developmental stage—it’s a lifelong psychological necessity. We need potential space in order to grow, change, and find new ways of being. It’s the space in which authenticity becomes possible—not through performance or compliance, but through experimentation and integration.

Unlike thinkers such as Kierkegaard or Sartre, who emphasise authenticity as an inward ethical or existential stance, Winnicott gives us a developmental and relational framework. He shows how our very capacity to be authentic depends on having had space—what he calls potential space—in which our emerging self could be met, mirrored, and tested in relationship.

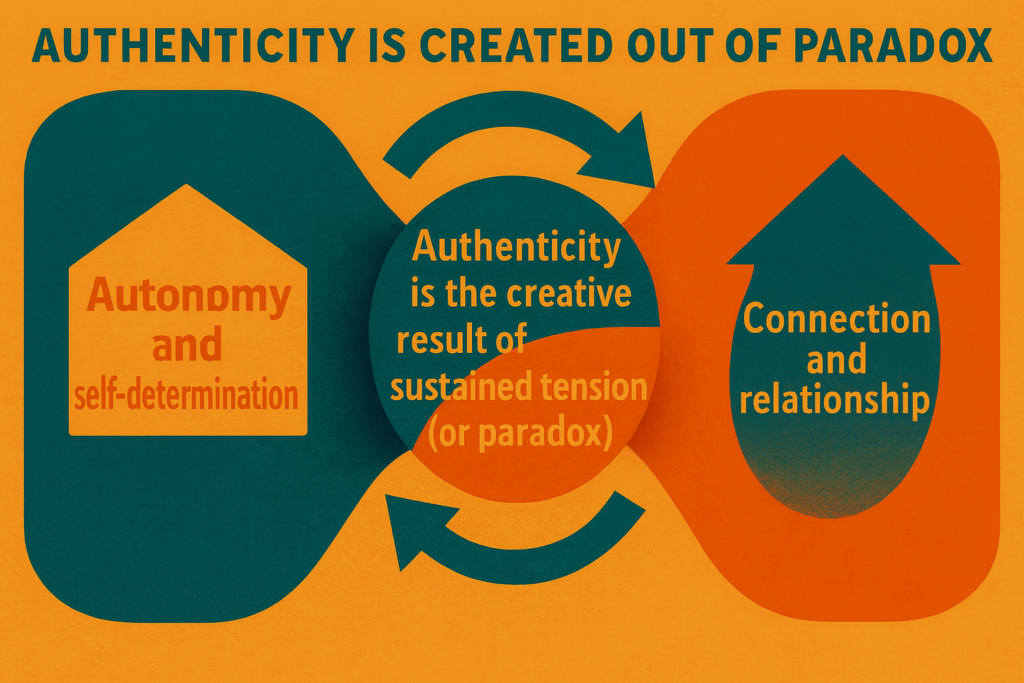

Authenticity as Paradox

At the heart of this process is paradox. As adults, we are constantly negotiating between autonomy—the need to assert and define ourselves—and connection—the need to belong, attune, and relate. Winnicott’s insight is that authenticity arises not by resolving this tension, but by sustaining it.

Potential space is the psychological terrain in which that paradox can be played with rather than split or denied. It’s where we test new behaviours, encounter feedback, and risk discovery. Without this space, we tend to collapse into either defiance (a rigid, isolating autonomy) or compliance (a performative, self-effacing connection).

This insight has direct implications for adult life. In coaching and leadership, I’ve seen again and again that the most meaningful transformations occur not when people double down on control or try harder to please—but when they learn to inhabit the middle ground with curiosity, awareness, and support.

Why This Matters for Coaches and Leaders

This understanding of authenticity has profound implications for how we support development—in ourselves and others.

If authenticity is not a fixed trait but a creative, relational process, then:

- As leaders, we are most impactful not when we perform a perfected version of ourselves, but when we remain open to feedback, contradiction, and complexity. Our presence—how we hold tension, uncertainty, or difference—shapes the potential space of a team or culture.

- As coaches, we are not simply uncovering a client’s “true self,” but co-creating the conditions in which new possibilities can emerge. We help hold the space where autonomy and connection can be safely explored—where a client can play with new ways of being without needing to prematurely resolve them.

This shift calls for a mindset that values ambiguity, dialogue, and emotional spaciousness. It suggests that authentic leadership isn’t about being definitive—it’s about being present to what is still unfolding.

A Practice, Not a Trait

In this sense, authenticity is not a trait.

It’s a practice—a way of inhabiting the space between.

As Nietzsche suggested, we are not given a self—we are invited to become who we are. But unlike the solitary heroism of that task, Winnicott reminds us that we become ourselves in the presence of others, through a creative and relational process of experimentation, imagination, and play.

This is where potential space matters most.

Not just as a theory of childhood, but as a living, breathing domain of adult transformation.